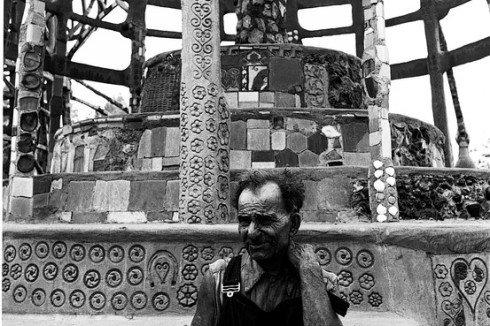

“I was going to do something big, and I did…You have to be good good or bad bad to be remembered.”

– Sabato “Sam” Rodia, 1952

On a sunny Sunday afternoon I convinced my girlfriend to head down to South Central L.A. with me to check out Watts Towers. Growing up in a gang-rife Los Angeles of the 1980s and early 90s where Crips and Bloods reigned supreme, children were taught to be afraid of South L.A. South Central was especially dangerous and anywhere south of the 10 Freeway was to be avoided at all costs. In the films and television of the 80s and 90s, “Don’t go south of the 10 (Freeway),” was a common repeated phrase.

Fortunately we disregarded the advice of my childhood and decided to pay a visit to Sabato “Sam” Rodia’s Watt’s Towers, a one-man 30 year creation spanning from 1921 to 1954. Visiting the towers really touched me. I wanted to get a feel for the human heart behind this intense labor of love.

Coincidentally the Watts Jazz Festival was in full swing on the Sunday afternoon when we made the trip down to South Central Los Angeles. Watts has a history of defiance, notably the Watts Riots of 1965, the L.A. Riots of 1992, and in a historically defiant work of outsider art, Watts Towers. The Towers have stood the test of time, a veritable fist in the sky against naysayers, vandals and multiple city demolition attempts.

On the Watts Jazz Festival’s stage a charismatic M.C. declared into the mike, “Don’t let the city officials fool you. We put this together ourselves without their help. We raised the money. We put this together for the people of Watts without help or assistance from the City of Los Angeles.” The attitude of the M.C. seemed directly reflective of Rodia and his Towers. Rodia worked alone and completed his masterpiece without the help or money of outsiders. It was his personal gift to South Central Los Angeles and the world.

Although the Towers and the surrounding park are on the map, as far as city officials are concerned, the people of South Central L.A. are a low priority, off the radar of city government. South LA residents’ marginalization in the past led to drug addiction, gang violence, riots and turmoil. The mostly middle-aged black attendees of the Watts Jazz Festival have survived living in a place that at times resembled a war zone. They continue to have a sense of quiet yet defiant pride. The Watts festival attendees seem to prove that holding your head high and holding your culture close is one of the only ways to overcome decades of adversity. What better way to show this sentiment then throwing a free Jazz Festival in the park, run by the people for the people. This idea seemed to go back to the Wattstax Festival of 1972 where admission was $1. They kept the admission cost low so that everyone who suffered the Watts riots 7 years earlier could afford to partake in the festivities.

Simon “Sam” Rodia was an Italian immigrant who began his new life in Pennsylvania in 1895. When his brother died in a coal mining accident, he moved west, living in Seattle and Oakland, where he and his wife had 3 children. A tiny man, at 4’11”, he worked with his hands as a tiler, logger and construction worker as well as finding work in railroad camps and rock quarries. Many of the skills he learned in his varied manual labor occupations would later facilitate the creation of his masterpiece.

When he divorced his wife around 1909, he left his family in Oakland, moving south to Long Beach. After a few years of living and working (including relationships with 2 women), he heard about a reasonably priced small plot of land for sale in Watts. At the time, Watts was not a desirable location to live because of its proximity to both rail road tracks and the light rail tracks for the Red Car, a street car which connected downtown Los Angeles with Long Beach. The street car and the railroad produced quite a bit of noise which made the nearby lot a difficult sell.

Rodia’s romantic relations with a woman named Benita dissolved and in 1921 he decided to buy the triangular plot located at 1761-1765 107th Street in South Los Angeles. He built a small house for himself on one side of the lot and feverishly began construction on his vision of 3 towers on the other. In the 20s he lived with a woman named Carmen. After she left him in 1927, he would remain alone for the rest of his life, dedicated to creating something great.

Rodia’s heroes were highly regarded Italians like Galileo, Marco Polo, Christopher Columbus and Michelangelo. He admired the Leaning Tower of Pisa and other noteworthy Italian architecture. He was determined to create something that matched the accomplishments of his idols. It was also rumored that he drank heavily after leaving his wife, and he felt the need of a monumental project to avoid a plunge into heavy drinking. Rodia came up with an idea to create a giant sculpture resembling one of Marco Polo’s ships.

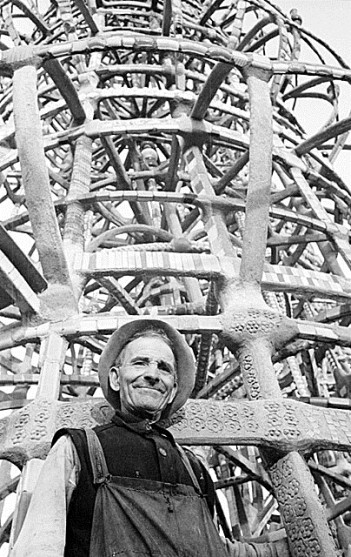

He built his Towers using a mixture of concrete, steel and wire mesh. He would bend steel using the nearby railroad tracks to anchor a makeshift vise. His basic masonry tools and his bare hands were his instruments to build. He decorated his towers and the walls surrounding the Towers with his neighbors’ discarded trash: glass bottles, broken kitchen platters, ceramic pottery and seashells from the beach 20 miles away. He constructed a stone oven where he baked bread as well as melted ceramic and glass items for decoration and construction of the Towers. His sense of humor is seen in his offbeat touches including a cement cowboy booted foot and teapot spouts jutting out of walls.

Rodia would also pay neighborhood kids in cookies or pennies for pieces of broken pottery and kitchenware. He was known to the children as the “3 Musketeers Man,” because at the time, a full-sized 3 Musketeers chocolate bar cost a nickel. If the kids brought him enough ceramic pieces, he would sometimes reward them with a nickel.

Rodia worked full time in a ceramics factory, the Malibu Tile Company in Santa Monica, and would collect ideal pieces to decorate his massive sculpture. He was fired from Malibu Tile when they discovered he was stealing such a large amount of supplies. He quickly lined up other work in the area in tiling, as a security guard and as a telephone line repairman. He diligently attended work full time and remained obsessed with his project during every free moment day or night for 30 years.

To make his commute to work quicker, he placed a circular police siren on top of his car. After successfully navigating South L.A.’s streets in an imposter squad car, someone reported him. The police came to investigate and he told the officers that he had never owned a car. The rumor was that he buried his car to avoid prosecution. It remained a rumor until it was confirmed in the 1990s, when the shell of a car was found buried behind one of his walls.

Despite his popularity with certain neighborhood children, he was often mocked by locals, dismissing his project as crazy or an eyesore.

Shrugging off the frequent ridicule, Rodia remained focused.

“Some of the people they say what is he doing? Some of the people were thinkin’ I was crazy, and some other people they say he’s gonna do something.”

– Sam Rodia

He would frequently walk the entirety of the railroad tracks from Watts to the rail road depot in Wilmington (about 15 miles one way), to collect broken bottles and other useful items on the side of the tracks. He used bottles of popular beverages such as 7-Up for green glass and Milk of Magnesia for blue glass.

His name was misspelled in a 1937 LA Times article calling him “Simon Rodilla.” History would correct his last name (Rodia), but unfortunately his incorrect first name (Simon) remained. He went by the nickname “Sam,” although his Italian given name was Sabato.

As Rodia’s project reached new monumental heights (his tallest Tower 99 1/2 feet tall) he ordained himself a minister and began orchestrating weddings, baptisms and other religious ceremonies in front of his towers. His ceremony had an unmarried couple entering the compound from one divided door frame and leaving simultaneously through one door. The ceremonies he performed were not recognized by the church or the State of California, but he drummed up a steady flow of marriages and baptisms nonetheless. On Sundays he would give sermons from a podium to any who would listen. Rodia built two fountains that spurted water. As the overflow of liquid seeped into his designs imprinted on the ground, it gave them an otherworldly feel.

According to our tour guide at Watts Towers, Rodia worked with his hands so frequently that his fingerprints were completely rubbed off. He bathed once a month in rubbing alcohol to get all of the building material off of his skin. He used a window washer’s belt and harness to climb the towers, and in his old age fell off one of the Towers in the 50s, breaking one of his hips. He remained committed and finished his project which he compared to “Marco Polo’s ship.”

On the side of the main tower is inscribed “Nuestro Pueblo” – “Our Town” in Spanish. He was fluent in Spanish and his Mexican neighbors thought that he was of Latino origin. He attended Italo-American society meetings in downtown Los Angeles so he managed to retain his Italian identity. It is curious that he named his creation “Nuestro Pueblo,” in Spanish instead of Italian. The Italian would have been “Nostra Città.” Simon Rodia was illiterate, dropping out of school at the age of 12 when he began working, so perhaps he became more accustomed to Spanish after his 50 years in the states or maybe he knew that more locals were familiar with Spanish. Perhaps it was a nod to the region’s Latino history or the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Monument on Olvera Street, the most historic street in downtown Los Angeles.

When completed, within the walls of Rodia’s Towers are 17 structures including 3 towers, a baptismal font, fountains and the four walls that surround the Towers. A city ordinance forbade a building taller than 100 feet so his tallest tower is 99 1/2 feet tall. The inner and outer walls as well as the ground are covered in Rodia’s personalized imprints – using a garden hose faucet to depict flowers, the metal backings of chairs and headboards to create intricate imprints and also hand-placed sea shells, glass bottles and tiles. Heart designs also feature prominently. When asked about the significance of the hearts, he replied, “You know.”

During WWII, in step with Japanese internment and widespread anxiety and paranoia, it was rumored that his creation was a clandestine radio tower used to communicate with the enemy.

After 31 years of labor, in 1948 his Towers were complete, ornately decorated and solid. Allegedly he frequently bickered with his neighbors, and some of the locals would even vandalize his project.

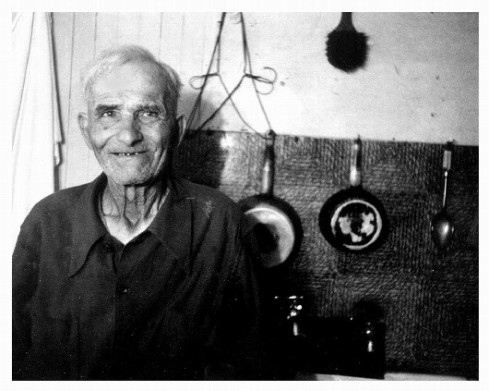

Finishing his masterpiece well into his 70s, he decided to relocate to Martinez, California (near his former home of Oakland) to be closer to his family. In 1954, he gave the plot of land to a neighbor, Luis Sauceda, and left his beloved Towers forever. One year later Sauceda sold the land to Joseph Montoya who wanted to convert the property into a taco stand that prominently featured the Towers, but this project never came to fruition.

In 1959 the Towers were condemned and slated for demolition, deemed “hazardous” by the City of Los Angeles. A few art advocates spearheaded by William and Carol Cartwright and Nicolas King, managed to raise $3000 to purchase the Towers. They orchestrated engineers to conduct a safety test. A crane was attached by rope to the main tower. It was decided that if the tower fell, then the Towers were unsafe. If the tower was left to withstand the intense force of the crane, then it would stay. Rodia’s Towers past the strength test with flying colors as the wheels from the crane were lifted off of the ground and the rope eventually broken with no damage to the tower besides a slight lean. His tower was jokingly dubbed, “The leaning tower of Watts.”

Sam Rodia happily conducted a few interviews with journalists and filmmakers about his Towers as they began to attract international attention in the 50s.

“I was going to do something big, and I did…You have to be good good or bad bad to be remembered.”

– Sabato “Sam” Rodia, 1952

Rodia attended a conference about the towers at UC Berkeley in 1961 and appeared satisfied about finally receiving some recognition although he never visited his Towers again after leaving Watts in 1954. Sabato “Sam” Rodia died July 16, 1965 about one month before the Watts Riots violently erupted.

Demonstrators push against a police car after rioting erupted in a crowd of 1,500 in the Los Angeles area of Watts. 14,000 national guardsmen were called in to disperse the rioting and over 100 square blocks were destroyed by arson over a 6-7 day period in August of 1965.

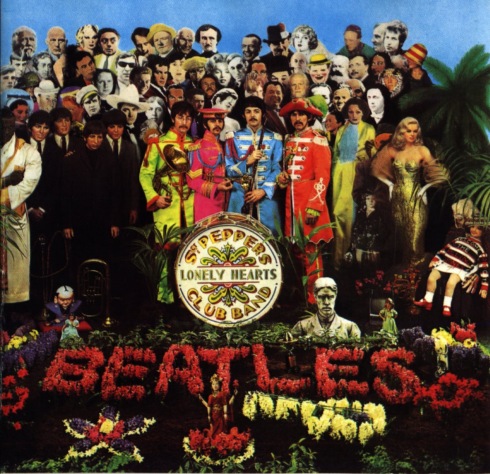

Two years later, a photo of Rodia was included on the iconic album cover of the Beatles, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band released in ’67 (Rodia is on the top row, far right, to the immediate left of Bob Dylan). Jann Haworth, the co-designer of the album cover was a native Angeleno, she included Simon Rodia as one of her personal contributions to the inspirational or historic figures included in the artwork.

Since the towers were proven safe, in 1975 the City of Los Angeles and the State of California took over the maintenance and conservation of the towers and they became a public heritage site. The immediate surrounding area became a park and arts center.

“Through the sheer force of the creative intelligence they manifest, the towers uplift the Watts community. They serve as an urban oasis…”

– American National Biography, A.N.B.

I thought about Simon Rodia and how his tenacity, character and personality reminded me of the way Italian-American writer John Fante, also an L.A. writer, described his own father, Nicola “Nick” Fante in his books. His father was a brick layer, often out of work during long winter months in Colorado. He drank plenty of “Dago Red” wine and was very proud at his intermittent accomplishments, constructing many prominent buildings in the Denver area. Many of Nicola Fante’s schools and churches still stand today in Northern California and Colorado.

In Dan Fante’s memoir about his family “Fante,” he recounts a tale of his Grandpa Nick in a bar fight with two Irishmen after they humiliated him. He smashed a bottle over one of the Irishmen’s head and bit the ear off another. He couldn’t handle being slighted or humiliated.

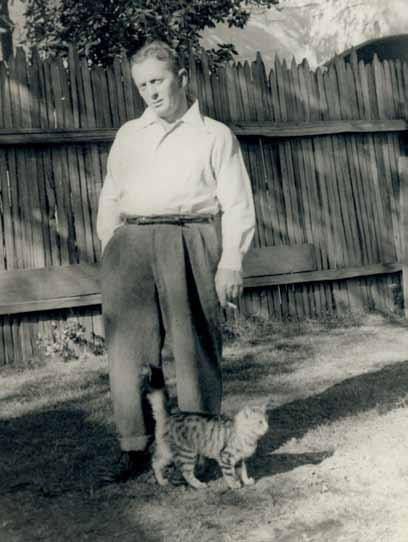

John Fante, Italian-American author and screenwriter. His father was a stubborn stonemason – Nicola Fante, and his son Dan Fante, another iconic Los Angeles writer – also incredibly stubborn, it runs in the family…

In John Fante’s book, “Full of Life,” he writes about his ferociously stubborn Italian father, who moves in with his son’s family in Los Angeles to help renovate their house when it became infested with termites.

“I felt his hot tears and the loneliness of man and the sweetness of all men and the aching haunting beauty of the living”

– John Fante, Full of Life

The ornery tenacity of Italian-American laborers like Nicola Fante and Sam Rodia has disappeared from today’s milk toast American society. Sam Rodia’s Watts Towers still stand, now respected but only after years of being considered the work of a crazy recluse. Rodia put up with the humiliation of being considered a laughingstock but remained ferociously dedicated to his art. After he was forsaken from his family, Rodia had a singular focus, building something he would be remembered for. In the still struggling South Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, his Towers remain a testament. They reveal the resilience of the human condition. They show that a neighborhood can survive racism, poverty, police brutality and riots. They show that a simple man can create, even a man with a broken heart.